Elicitation

Excellent software is the result of well-executed design based on excellent requirements. Excellent requirements result from effective collaboration between developers and customers. This requires that all parties know what they need to be successful and understand and respect what their collaborators need. The business analyst forges this collaborative partnership.

A partnership requires that partners speak the same language, so learn the language of the business. Put together a glossary of terms, including synonyms, acronyms, and abbreviations.

A data dictionary stores more detail about terms in the glossary. It’s a shared repository that defines the meaning, composition, data type, length, format, and allowed values for data elements used in the application.

Stakeholders

In most cases, more than one category of user, or user class, exists. Some people call user classes stakeholder profiles or personas. User classes needn’t represent humans; they can also be external systems. Document user classes and their responsibilities, characteristics, numbers, and locations.

Direct users operate the product. Indirect users receive output from the product without touching it themselves.

The analyst works with the business sponsor to select representatives of each user class, known as product champions. Product champions gather requirements for all users in their class, so make sure they have the authority and trust required to do that. Ideally, product champions are actual users of the system.

If the product targets customers outside the organization developing the software, focus groups can take the place of product champions. A focus group is a representative group of users who convene to generate input and ideas for requirements.

The project’s decision makers must resolve conflicts between user classes. The primary stakeholders, also known as favored user classes, get priority.

Disfavored user classes are groups who aren’t supposed to use the product for legal, security, or safety reasons. Functional requirements for these user classes focus on making it hard for them to use the product. Examples are authentication to keep people from using the system at all, and authorization to prevent them from using specific features. In this context, some people talk about abuse cases that the system should prevent instead of use cases that make something possible.

Lack of adequate stakeholder involvement leads to an expectation gap, a gulf between what customers need and what developers deliver. To keep this gap to a minimum, arrange frequent contact points with product champions. Don’t limit this interaction to requirements, but involve users in as many activities as sensible.

Techniques

Elicitation is the process of identifying the needs and constraints of the various stakeholders. It focuses on how they do their work and how the system helps support that work. For any given project, you’ll probably need to use more than one of the following elicitation techniques:

- Hold interviews with individual stakeholders. Come prepared with questions and use active listening [Rogers1951]. When replacing an existing system, a good question is what annoys the user the most about it. It also helps to come with a draft model or prototype that the user can critique. Assign someone not actively participating in the discussion to take notes.

- Identify events. An event list identifies external events that trigger behavior in the system. Events originate from users, time, or external systems.

- Hold workshops with multiple stakeholders. These are especially useful for resolving disagreements, so hold them after using other techniques that surface those disagreements. Workshops may take on a life of their own, so refer to the business requirements to enforce scope and focus on the right level of abstraction for the session’s objectives. Smaller groups work faster than larger ones.

- Observe users do their work (ethnography). This helps understand the social and organizational context in which the work takes place. Limit sessions to two hours and focus on high-risk tasks. Use silent observations when you can’t interrupt users with questions.

- Distribute questionnaires. These are cheaper than alternatives when surveying large numbers of users. Their analysis can serve as input for other techniques that target smaller numbers of users.

- Analyze existing systems. Attempt to find the underlying need for offered features and assess whether the new system must address the same needs. Problem reports can give good ideas.

- Analyze existing documents. Examples are requirement specifications, business processes, user manuals, corporate and industry standards, and comparative reviews. Remember that documents may be out of date or incorrect.

- Analyze interfaces with external systems. This analysis gives technical requirements around data formats and data validation rules.

- Reuse requirements based on pre-existing business rules.

Different techniques work better for different user classes.

Elicitation is usually either usage-centric or product-centric. The usage-centric approach emphasizes understanding and exploring user goals to derive functionality. The product-centric approach focuses on defining features expected to lead to marketplace or business success.

A feature consists of one or more logically related system capabilities that provide value to a user and are described by a set of functional requirements.

— [Wiegers2013]

In usage-centric requirements elicitation, we capture user requirements in use cases. A use case describes a sequence of interactions between a system and an actor that results in value for the actor. An actor is a person or external system that interacts with the system.

A use case consists of one or more scenarios. The main success scenario describes the happy path of the interaction. Secondary scenarios, or alternative flows, describe variations in interaction, including those for error conditions. Each scenario has a description, trigger, preconditions, interaction steps, and postconditions. Exceptions describe anticipated error conditions and how the system should handle them.

Users may not be aware of all preconditions, so look to other sources as well. Business rules may drive some preconditions, like what role the user must have to perform the scenario. They may also define valid input values for or computations performed during the interaction steps.

Users know about those postconditions that relate to the value created for them, but those are usually not the only ones. Developers and testers often need postconditions that aren’t as visible to the user.

Activity or state diagrams can depict the interactions steps in a use case scenario.

The frequency of use gives a first estimation of concurrent usage and capacity requirements.

For products where the complexity lies outside user interactions, you may need other techniques besides use cases, like event analysis.

Stakeholders must establish acceptance criteria, predefined conditions that the product must meet to be acceptable. Without acceptance criteria, there is no way of knowing whether the product meets the requirement. Boundary values are especially interesting.

Use cases capture user requirements. They focus on the externally visible behavior of the system. To complete development, we need more information. The extra information takes the form of functional requirements that support the user requirements.

One example is about reporting. A use case may show that the system compiles a report for a user class, but not the details of the report. A report specification describes the purpose and contents of a report. A dashboard uses multiple textual and/or graphical representations of data that provide a consolidated view of a process. Dashboards and reports may show predictive as well as descriptive analytics, which require understanding the underlying models and statistical calculations.

Quality attribute requirements

Quality attributes define how well the systems works. Examples are how easy it’s to use, how fast it executes, and how often it fails. External quality attributes are important to users, while internal quality attributes are important to developers, operators, and support staff.

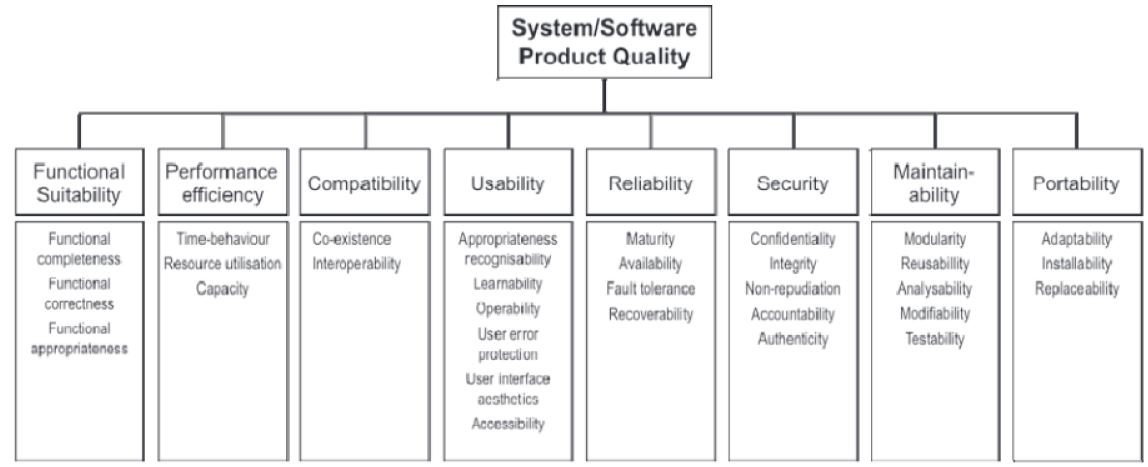

[ISO25010] defines eight quality characteristics, each of which consist of several quality attributes. Note that the first characteristic is functional suitability, which refers to functional requirements. ISO recommends you select a subset of quality attributes that are important for your system. For instance, hard real-time systems have stringent performance and efficiency requirements. Safety-critical systems place more emphasis on reliability.

Eliciting requirements for quality attributes is difficult. When given a choice, stakeholders always opt for the fastest, most reliable, most secure, etc. Ask them instead what defines unacceptable performance, reliability, security, etc.

The term dependability covers the related quality attributes of availability, reliability, safety, security, and resilience. Availability is the probability that the system is up and running and able to deliver useful services to users at any given time. Reliability is the probability that, over a given period of time, the system delivers correct services as expected by users. Safety is a judgement of the likelihood that the system doesn’t cause damage to people or the environment. Security is a judgement of the likelihood that the system can resist accidental or deliberate intrusions. Resilience is a judgement of how well the system can continue offering its critical services in the presence of disruptive events.

Quality attributes are emergent properties of the sociotechnical system, which contains hardware, software, and non-technical elements such as people, processes, and regulations. Sociotechnical systems are so complex that you can’t understand them as a whole. Rather, you have to view them as layers: equipment, operating system, networks, applications, business processes, organization, and society.

The society layer contains governments, which mandate that organizations follow certain standards that ensure products are safe and secure. Governments establish regulatory bodies with wide powers that enforce compliance with these rules.

A constraint places restrictions on the design or implementation choices available to developers. Constraints can come from stakeholders (like compliance officers), external systems that the product must interact with, or from other development activities, like transition and maintenance.

It’s easy to miss requirements:

- Assumed requirements are those that users expect without explicitly expressing them. Quality attribute requirements are often assumed.

- Implied requirements are those that are necessary because of another requirement.

- Different user classes have different requirements, so make sure to involve representatives of all user classes. For instance, the sponsor may not use the product directly, but may need KPIs that the product must collect measurements for.

- High-level requirements are often too vague. Decomposing them into more detail may bring to light other requirements, including implied ones.

- Another source of missed requirements stem from error conditions.

- A checklists of common functional areas may help to increase coverage.

Requirements may change as customers learn more and as the business evolves. See change management.

Try to keep design out of the requirements as much as possible. For instance, focus on user tasks rather than user interfaces. You can only go so far with that, however. For instance, sometimes you need to design (part of) the architecture to enable analysis of requirements. When dealing with systems of systems, you need to know whether the requirement is for the software or for a non-software component. You also need to know what the interface requirements are.

Reject the solutions that stakeholders often offer. Instead, describe the underlying needs that those solutions address. In other words, understand the job the customer is hiring the software to do [Christensen2016]. The Five Whys technique may help to go from a proposed solution to the underlying need [Ohno1988].

Reuse

It’s possible to reuse requirements, just like other software development artifacts. Reuse improves quality and increases productivity, but comes with its own risks, like pulling in unneeded requirements via links to related requirements.

Requirements reuse ranges from individual requirement statements to sets of requirements along with associated design, code, and tests. Reused requirements often need modification, like changing their attributes. You can copy requirements from another product or from a library of reusable requirements, or you can link them to a source. The latter makes it hard to change the reused requirements.

Glossaries and data dictionaries are good sources of reusable information. Common capabilities in products, like security features, are also good candidates for reuse. Software product lines, a set of software products in a family, share a lot of functionality and thus opportunities for reuse.

If the product replaces another system, then you’re always reusing requirements, even if implicitly. However, you shouldn’t carry over all requirements without evaluation. Look for usage data that allows you to remove features that are rarely used. Check features against the business objectives, since these may have changed. Also look for new requirements, including transition requirements. Remember that existing systems set expectations for quality attributes, like usability, performance, and throughput.

Requirement patterns offer a different form of reuse. They package considerable knowledge about a particular kind of requirement in a way that makes it convenient to define such a requirement. A pattern gives guidance about applicability, an explanation about the content in the requirement, and a template for a requirement definition. It also gives examples, links to other patterns, and offers considerations for development and testing.

While reuse saves you time, making requirements reusable costs extra time. Requirements management tools can make reuse of requirements easier and help with finding reuable requirements.